Preface: Rental prices are important not only for renters and apartment owners, homeowners and the building industry, but also because they greatly influence the consumer price index (see this and this). As the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco noted today:

Part of the drop in measured core inflation is undoubtedly due to the deceleration in the price of housing. The declines in housing inflation have been more profound than in core inflation. The 12-month percentage change in rents and owners’ equivalent rents has come down from 4.5% in February 2007, at the height of the housing bubble, to 0.3% in February 2010. This decline in the rate of housing price increases reflects reduced upward pressure on rents, which in turn is due to historically high vacancy rates for rental properties. Because house price inflation is now below core inflation, it drags down the overall level of core inflation.

There are many factors which affect rental prices, including: (1) the general health of the economy; (2) demographics; (3) housing strength; (4) population growth; (5) migration patterns; and (6) wealth distribution.

The General Health of the Economy

The relation between housing sales and rentals cannot be examined in a vacuum. The general health of the economy is important as well.

For example, as the Newark Law Review notes:

During the depression years, there was a widespread tendency among tenants to seek reduction of the previously established rental for the premises they occupied, basing their pleas on a general shrinkage of incomes. Many of these requests were complied with, landlords realizing that rentals stipulated in boom days before the crash were far above the price for which other premises were available.This is not just of historical interest, given that many financial experts think this could be worse than the Great Depression. And see this.

In addition, banks still are not lending to most individuals (indeed, the Fed is intentionally tying up excess reserves so they won't be circulated in the economy). So for now, the credit crunch is still playing a role.

The effects of a credit shortage are complicated.

As USA Today noted in 2008:

Another writer listed other potential effects of a credit shortage:Several factors are driving up demand for rentals:

***

•Renters are finding it harder to buy. Many renters can't qualify for an affordable mortgage because of stricter lending rules that call for larger down payments and excellent credit. The days of getting a home with no money down or with other unconventional loan structures are gone.

Lenders have turned more cautious for good reason: Foreclosures are up, and each of them costs lenders an estimated $50,000, on average, in processing fees, liquidation-sale price cuts and other costs, according to the Center for Responsible Lending.

"We've seen demand for rental housing go up," says Mark Obrinsky, chief economist at the National Multi Housing Council. "The ownership side is retrenching, and we're seeing the demand going to the rental side. There's a lot of hesitancy to buy. Others can't get (financing), so they're remaining renters longer."

People who can't sell their home may try to rent it out. (Pushes rental prices down.) [and] People who buy cheap homes for investment purposes may rent them out until the market recovers. (Pushes rental prices down.)On the other hand, if the economy improves more quickly than most imagine, rental prices might be pushed up along with everything else.

Demographics

The American population is rapidly aging.

As I wrote in October:

Seniors have less income from wages, but have had longer to save money and invest. However, a report by the Center for Economic and Policy Research shows that most baby boomers have accumulated little to no wealth.As I have previously noted, Japan's population is rapidly aging, and the U.S. age pyramid - while not as bad - is not nearly as young as that of Brazil or India's:

The chief economist for Standard and Poor's is now confirming the importance of national demographics:Which countries have the best demographics?

Let's start by looking at the "age pyramid" for the United States. The following 2 charts from the National Institutes of Health shows that the population is aging:

This graphic (courtesy of Ed Stephan) shows the U.S. age pyramid from from 1950 through 2050:

male female

Population of the United States, by Age and Sex,

1950-2050 (millions)

information source: International Data Base, U.S. Census Bureau;

supplied pyramids were modified using Canvas, GraphicConverter and GIFBuilder.[If you can't see the dates at the bottom of the pyramid, click here].

As NIH notes:

The first of the postwar baby boom cohort, born 1946–1964, will turn 55 years in 2001. In just three decades, an extraordinary change in the age structure of the United States is anticipated. By 2030, one in five persons (20% of the U.S. population) will be aged 65 or older, increasing from the present ratio of one in nine persons (12.8%). The number of persons in the 65 and older age group will more than double, increasing from the current 34 million persons to 70 million persons. Moreover, within the older segment of the population, because of longer life expectancy and additional persons reaching older ages, there will be age shifts resulting in the 85 and older population more than doubling in size from 4.3 million persons to approximately 8.9 million persons.An aging U.S. population means less productive workers, less big-spending consumers, and more dependent elders...

Brazil has a much younger age demographic.

And India's is even younger than Brazil's.

The following chart shows that Japan has the worst demographics of all, with a staggering percentage of elderly who need to be taken care of by the young:

Chart 2: Old Age Dependency Ratios for Selected Countries

Source: http://data.un.org/

In other words, America's age demographics aren't as bad as Japan's, but they aren't helping, either.But I don't think [a lost decade in the U.S. is] as likely over here. For one thing, one of the problems in Japan was the demographics. And we don't have the problem of a declining population to deal with, although the labor force is going to slow down considerably as soon as the baby boomers retire.

No wonder:

David Rosenberg from Gluskins Sheff expects Americans to retrench ferociously as 78m baby boomers face the looming threat of penury in old age.In addition, pensions are getting killed, and because the states are already experiencing massive budget deficits that cannot cover education and other expenses, something has to give. I am not convinced that pensioners are going to get paid 100% of what they were promised. Same with social security benefits.

Does that mean people will receive drastically reduced benefits compared to what they were promised, that taxes will skyrocket, or both? Any way you look at it, the American population is quickly greying, and a high percentage of seniors won't have much to spend on housing.

As the above-quoted Forbes article states:

Pittsburgh has the country's cheapest metropolitan area rental units. Lessees there pay a median monthly rent of $608, less than half of San Jose's.

This is partly because Pittsburgh has struggled to rebuild its economic base after the loss of its steel industry, and residents are aging or leaving the city.

"The bottom line is that Pittsburgh is undergoing a sea shift in its economic base," says Susan Wachter, a real estate professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. "Rents are relatively low because it's in a state which is losing population, and it is simply not doing well."

One final factor: long-term care facilities for seniors are growing like gangbusters:

Assisted living facilities are a relatively new housing phenomenon. Although they were extremely rare even ten or fifteen years ago, they've become the fastest-growing and most popular elderly residential product type. Although actual numbers are sketchy, an estimated one million seniors currently reside in approximately 40,000 assisted living facilities, as compared with only 600,000 who did so only ten years ago, when there were about one-quarter of these projects nationwide. And looking ahead, experts estimate that by the year 2020, 14 million of us will require this kind of housing, double the number who do so today.Such facilities will soak up some of the housing demand for the elderly, which also argues for lower rental prices.

Housing Troubles

Falling home prices are generally correlated with rising rental prices. As Forbes noted in 2008:

Sinking house prices often send rents soaring ...Moreover, when there are a lot of foreclosures in a given area, a lot of people are evicted from their homes, and must scramble to find rentals. This usually leads to higher rental prices, as surging demand chases a fixed supply.

As the above-quoted USA Today pointed out:

The most brutal real estate slump in decades is reverberating through the rental market. Renters in properties that are being foreclosed on are being evicted. Homeowners forced into foreclosure are becoming tenants again and driving up rents. And renters not yet ready to buy a home — shut out by stricter lending rules or hoping to buy after prices fall still further — are creating a dynamic shift: Even as real estate is sputtering, the rental market is surging.On the other hand, as CNN noted in 2008 that foreclosures may make more rental properties available, thus tending to reduce rental prices:

So how is housing going to do?"The major factors having an impact on housing prices are foreclosures, which make more rental property available," said Owen Johnson, president of Investment Instruments, "and also foreclosures that are not happening."

In the latter case, according to Johnson, many speculators bought properties to "flip," selling them quickly in a rapidly appreciating market. In some Sun-Belt areas, investors bought condos and other properties while they were still in development, to sell when a project finished.

Other investors bought existing single-family homes or other properties, intending to do cosmetic improvements and then sell them at a profit. But before they could do that, the slump hit, and home values dropped. Instead of selling at a loss, investors of all stripes are now renting them out.

Well, as the Washington Post noted last week, things aren't all rosy:

Indeed, the S&P Case Shiller Futures Index forecasts that housing won't bottom until May 2011:The [Case-Shiller] report is "mixed," David M. Blitzer, chairman of the index committee at Standard & Poor's, said in a statement. The "rebound in housing prices seen last fall is fading." And given the data, he said, "we can't say we're out of the woods yet."

Housing analysts are worried that an expected increase in foreclosures hitting the market could put pressure on prices this year. Also, a Federal Reserve program that has kept interest rates low ends Wednesday. If mortgage rates rise later this year as expected, some potential buyers might stay on the sidelines.

Home sales have been weak since a tax credit for first-time home buyers was initially scheduled to expire in November. Existing-home sales have fallen 23 percent since then, for example. Congress extended the tax credit, giving buyers until April 30 to sign a contract for a home, and expanded it to more buyers. But "the second credit, up to now, is having minimal effects," said Patrick Newport, an economist with IHS Global Insight.

Many buyers at the tipping point of making a home purchase probably took advantage of the tax credit the first time, Dye said. "That group now has been used up. I would expect to see a smaller marginal effect from the tax credit going forward," he said.

Even if home prices rise during the spring buying season, they are likely to fall again during the second half of the year, analysts said. IHS Global Insight is expecting prices to fall another 5 percent this year. "There is some turbulence out there that I am concerned about," Dye said.

Specifically, the Case Shiller Futures Index assumes that housing prices will remain strong for the first half of the year - while various Fed programs are still in effect - and then fall sharply until they hit bottom in spring 2011.

And - contrary to what many assume - the foreclosure crisis is far from over.As I wrote in September:

And see this article from Time, this chart from Credit Suisse:The foreclosure problem in American is not just subprime mortgages. True, banks have been holding on to their foreclosed properties for months, but now they're getting ready to release them onto the market, which could depress prices for existing homeowners, further driving them underwater. But that's not what I'm talking about.

There are huge tidal waves of defaults on option arm, alt-a, and other types of loans coming (see this and this).

But even that is arguably not the main problem.

Perhaps the biggest problem is that the crash in real estate and rising unemployment together form a positive feedback loop. As McClatchy and the Associated Press note, foreclosures rise as jobs and income drop.

As former chief IMF economist Simon Johnson points out, there is a vicious cycle also exists between unemployment and property foreclosures:Unemployment is always a lagging indicator, and given the record low number of average hours worked, it will turn around especially slowly this time. Until then, people will continue to lose their jobs and wages will remain flat, and any small rebound in housing prices is unlikely to help more than a few people refinance their way out of unaffordable mortgages. So unless the other part of the equation – monthly payments – changes, the number of foreclosures should just continue to rise.Indeed, the Washington Post notes:

The country's growing unemployment is overtaking subprime mortgages as the main driver of foreclosures, according to bankers and economists, threatening to send even higher the number of borrowers who will lose their homes and making the foreclosure crisis far more complicated to unwind.And see this.

Some economists give 5% as the magic number: when unemployment declines to 5%, then unemployment will no longer be such a huge contributor to foreclosures.

But Moody's forecasts that unemployment will not go back down to 5% until 2014.

Indeed, unemployment could be a problem for many years to come.

Similarly, the the chief economist for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce - Martin Regalia - "thinks that it could be five years before the U.S. economy generates enough jobs to overcome those lost and to employ the new workers entering the labor force", according to McClatchy.

![[YouAreHere.jpg]](http://www.marketoracle.co.uk/images/2009/May/us-housing-13_image021.jpg)

Indeed, as David Rosenberg writes:

There were over 158,000 bankruptcy filings in the personal sector in the U.S. [in March] (that’s 6,900 per day!) which was a 35% surge over February’s result and up 19% from last year’s elevated levels. This also shows the extent to which fewer people are attempting to save their homes. They realized that their mortgage payments are not affordable and their attitudes towards residential real estate as a viable retirement asset have been altered permanently as many now see their house as nothing more than a debt-laden ball and chain.(Rosenberg also points out that while skyrocketing unemployment might be slowing, wage deflation is just beginning).

Finally, Calculated Risk writes today:

On The Other Hand ...From Diana Olick at CNBC: Let the Short Sales Begin

I'm ... starting to hear rumblings among the number crunchers that the wave of foreclosures we keep hearing about is about to hit with a thunderous roar.I don't know about a "thunderous roar", but I do think we will see more distressed sales soon. Most trustee sales seem to be "postponed" each month, and perhaps the lenders were just waiting for the HAFA short sales program to begin. That program started today ...

Servicers are ramping up the mod process and pushing those who don't qualify out the door more quickly than ever.

In really bad times, people who are evicted from their houses will not rent. Instead, they will move in with friends or family for some time.

As the Wall Street Journal explained last October:

Driving the change [i.e. large numbers of rental vacancies and lower rents] is the troubled employment market, which is closely tied to rentals. With unemployment at 9.8% -- a 26-year high -- more would-be renters are doubling up or moving in with family and friends during periods of job loss. Landlords have been particularly battered because unemployment has been higher among workers under 35 years old, who are more likely to rent. Nationally, effective rents have fallen by 2.7% over the past year, to around $972.

As Zack's Investment Research writes:

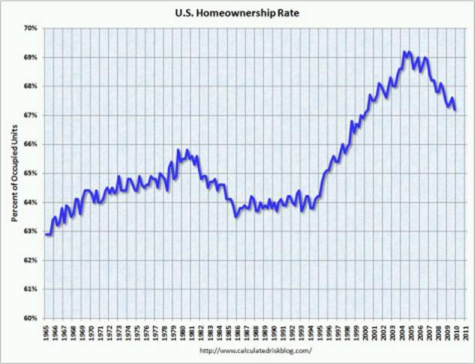

A smaller percentage of Americans owned their own homes in the 4th quarter of 2009 than at any time since 2000. In the 4th quarter 67.2% of Americans owned their own home, down from 67.6% in the third quarter and two full percentage points below the peak set in the fourth quarter of 2004.

As the first graph below shows (from Calculated Risk) ...:

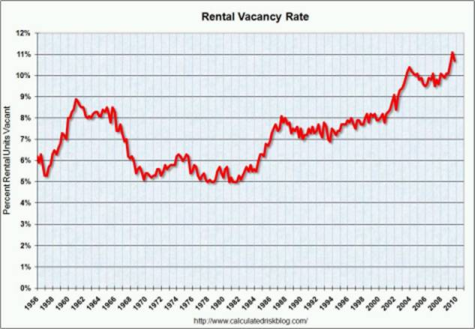

So where have all these people gone who are no longer homeowners? It does not appear that they are moving into apartments or rental housing. As the second graph shows (also from Calculated Risk), the rental vacancy rate is now at 10.7%. While that is down from the record level of 11.1% in the third quarter, it is up from 10.1% a year ago, and the 7-8% range that was normal for most of the 1990s ...

In other words, the correlation between falling home prices and rising defaults, on the one hand, with increasing rental demand and higher rental prices, on the other hand, doesn't hold in a really tough economy.***

It thus appears that many of the people who used to own their homes, and no longer do, are doubling up with friends and family. This is probably not their first choice of living arrangements, but they are doing so because they have no other choice economically.

American Population Growth is Slowing

The U.S. Census Bureau notes:

The U.S. population growth rate is slowing.

Despite these large increases in the number of persons in the population, the rate of population growth, referred to as the average annual percent change,1 is projected to decrease during the next six decades by about 50 percent, from 1.10 between 1990 and 1995 to 0.54 between 2040 and 2050. The decrease in the rate of growth is predominantly due to the aging of the population and, consequently, a dramatic increase in the number of deaths. From 2030 to 2050, the United States would grow more slowly than ever before in its history.

A lower population growth rate would tend to argue for lower rental prices, since it means less new residents looking for housing.

Indeed there is somewhat of a "reverse migration" occurring. For example, last year there were many stories of immigrants returning to their native countries. Of course, if the American economy substantially strengthens, this trend will stop.

"Dust Bowl in Reverse"

A "dust bowl in reverse" has also occurred, where people are moving out of the West and back to the mid-West.

As California state senator George Runner pointed out last year:

Indeed, a lot of people are moving to places like Oklahoma. As Michael Roston writes:A recent Sacramento Bee article cites a reverse migration to the Mid-west. This marks a stunning reversal of the historical trend of migration into California - especially during the Dust Bowl that sent hundreds of thousands of Midwesterners west toward the Golden State.

During the Dust Bowl, people left states like Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma because a drought left the once fertile soil barren and bone-dry. The livelihoods of the farmers shriveled with the crops, and families found themselves in destitution. They sought the greener pastures of California. But where the Dust Bowl of the Great Depression sent a massive migration of Midwesterners to California, the current economic hardship is now driving residents back to the Midwest.

In fact, between 2004 and 2007, California lost 275,000 residents to the former Dust Bowl states that were once responsible for the state’s huge population growth. While California was once seen as the place of hope for a better life, Californians are now looking elsewhere for opportunity...

The Tulsa World noted in December:The state added 43,025 residents from July 2008 to July 2009, the largest annual increase this decade.

The annual increase also reverses the one-year dip when the population failed to increase more than it did the previous year.

Overall, the Census Bureau estimates the Oklahoma population was 3,687,050 in July 2009 compared to 3,644,025 in July 2008. The annual population increase was 39,780 in 2007 and 34,238 in 2008.

Most of the overall population increase was fueled by persons moving to Oklahoma from other states, defined as domestic migration.

Domestic migration accounted for 18,345 new residents to the state with international migrants accounting for 5,340 additional people.

It’s not quite gangbusters, but it shows that the state known more for the Dust Bowl than for economic opportunity has turned itself around in a lot of ways. The Oklahoman’s crack Database Editor Paul Monies put together some visualizations of the differences in population between the Oklahoma of the Great Depression and the the Oklahoma of the Great Recession. His newspaper went on some months later to reflect triumphantly in an editorial:

Time was when Oklahomans fled to California in great numbers, so much so that the Golden State tried to put a stop to it. Now Californians are moving east; some of them are landing in Oklahoma. Cox says that in every year during the 2000s, Oklahoma gained net domestic migrants from California.

The South has also been hit hard. As the Wall Street Journal noted last month:

The recession has halted the dominant migration trend of recent decades, turning once-hot destinations such as Las Vegas and Orlando, Fla., into some of the country's losers.On the other hand, the Journal notes:

***

The reversal of migration in former housing-boom cities could aggravate their real-estate downturns. A separate report released by the National Association of Realtors on Tuesday showed that February real-estate sales and prices were hit harder in the West and South—areas that have seen big reductions in migration.

The shifts represent a radical departure from the migration patterns that had made cities such as Las Vegas and Orlando some of the country's fastest-growing. For decades, people have been leaving colder Northeastern and Midwestern states, either to retire or to chase better weather and jobs in the South and West.

"It's unprecedented to see areas like Las Vegas and Orlando, just blue-chip destinations for anybody who wanted to move, to stop and stay stopped over a couple of years," said William Frey, a demographer with the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank.

In many cases, cities in the Midwest and Northeast are gaining because residents are locked in place. With depressed home prices and a dearth of out-of-state job offers preventing departures, even a modest number of people moving in can drive gains. The Boston area, for example, swung to an inflow of about 6,800 in 2008-2009 from an outflow of about 46,000 in 2004-2005. The Chicago area's outflow narrowed to about 40,400 from about 77,400.The most-recent official U.S. Census Bureau population growth rates for different states - between July 1, 2008 to July 1, 2009, and for earlier periods - are available here, and here is a summary.

This factor weighs in favor of higher rental prices in the Midwest and Northeast, and lower rental prices in the West and South.

Back to the Country?

For hundreds of years, people have migrated from rural areas to the cities in search of better employment.

Will this change?

Sean Riskowitz argues that it already has:

Data released by the U.S. Census Bureau reveals a reverse urban migration trend in the country.Again, even if Riskowitz's interpretation of the data is correct, such a trend might be reversed if the economy strengthens.

This interactive graph paints the picture.

The recession has played a big role in determining migration trends in the U.S., with most people either staying where they are or returning to where they came from, particularly in big cities. The New York area lost a net 100,000 people in 2009, (down from 220,000 in 2007) while Los Angeles lost a net 80,000 (down from a massive 222,000 in 2007). Chicago lost a net 40,000 residents which is in line with the 52,000 the recession sent packing in 2007. This runs contrary to historical data which shows a net migration of people to big cities, rather than away from them.

Reverse urban migration will decrease the supply of labor and consumers in the cities which could result in lower prices in terms of real estate and consumer goods, not to mention services such as restaurants.

But there may also be longer-term trends arguing for counter-urbanization.

Oxford University's Geography Dictionary defines counter-urbanization, and gives some good arguments for it:

The movement of population and economic activity away from urban areas. The push factors include: high land values, restricted sites for all types of development, high local taxes, congestion, and pollution. The pull factors offered by small towns are just the reverse: cheap, available land, clean, quiet surroundings, and high amenity. Improvements in transport and communications have also lessened the attractiveness of urban centres, and commuters are often willing to trade off increased travel times for improved amenity. Furthermore, with the ageing of populations in the West, many no longer need to travel to work.Some argue that technology will encourage counter-urbanization. However, Bill Gates has famously said:

In advanced economies, there have been swings in the directions of net migration between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, although the timing of these shifts varies spatially. The USA, for example, saw counter-urbanization the 1970s, and concentration in the 1980s, followed by further deconcentration in the 1990s (Lewis, Geography 85). The migration balance will also be affected by government policy which suggests that 60% of new housing should be on brownfield sites, and 40% on greenfield (Department of the Environment 1996 Household Growth).

I thought digital technology would eventually reverse urbanization, and so far that hasn't happened. But people always overestimate how much will change in the next three years, and they underestimate how much will change over the next 10 years.If the U.S. economy really tanks to the point that distribution systems are disrupted, then people may either move out in the country (to grow their own food and locate their own water) or into the middle of the big cities (where they can get by without gas, and pool resources with others).

Obviously, if it occurs, counter-urbanization would lead to a decrease in demand for urban rentals. But it is too early to know how these trends will play out.

Wealth Distribution

The polarization of America's wealth distribution is more extreme than it is has been for many decades. In other words, not only have the rich gotten richer and the poor gotten poorer, but much of the middle class has disappeared.

So most people have less to spend on housing. The wealthy are likely going to buy, not rent, so they shouldn't play a part in the analysis.

That may argue for low-income and modest rentals doing well as most people become more frugal.

Obviously, many other factors influence how desirable a given locale is.

Silicon valley rental prices boomed during the dot com era. Washington D.C. is currently booming, due to the increased government involvement in the economy. As the Wall Street Journal writes:

Some cities accustomed to losing people are showing net gains. The government's growing role in the economy has benefited the Washington, D.C., area, which drew 18,200 residents from other states, its first net gain since 2002.

If the "next big thing" is centralized in one or a few areas, then rental prices could skyrocket in those areas.

Forbes points out that areas with a high number of apartment-to-condo conversions have higher rental prices:

And factors such as the amount of crime, how good the schools are and percentage of public housing will always affect rental prices.Signing a lease is also costly in some Florida areas. Miami and Orlando fetched monthly rents of $1,031 and $981 respectively.

The race to build condos is partly to blame, says Sean Snaith, director of the Institute for Economic Competitiveness at the University of Central Florida.

"Miami and Orlando were two pretty hot areas when the housing market was raging for conversion of apartment stock into condominiums," he says of the mid-decade housing boom. "So that reduced supply."

Rental experts note that small changes can affect rents:

Where To From Here?There are unique dynamics to the rental market, according to Johnson. Rents rise and fall independently of home prices. And there's often a push-pull to rental amounts: They're pushed up when foreclosures put homeowners back in the rental market but pulled back because the supply of rentals increases.

And, while national figures tend not to be too volatile, local markets can record large swings, as they did in 2007, when four of the 10 markets covered recorded double digit gains or losses.

Sometimes small events can leverage large changes, according to Johnson. "If MIT opens a new dormitory, for example, it can decrease rents substantially all over the Boston area," he said.

Pulling just a few hundred students out of the rental market in Cambridge (where the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is located) cascades down across many neighborhoods. Suddenly, there are a lot of empty apartments in the area, and renters from other places move in, increasing inventory in their old neighborhoods.

The Wall Street Journal writes:

Calculated Risk comments on the Wall Street Journal story, noting:Apartment rents rose during the first quarter, ending five straight quarters of declines and signaling the worst may be over for the hard-hit sector.

Nationally, the apartment vacancy rate stayed flat at 8%, the highest level since Reis Inc., a New York research firm, began its tally in 1980.

Reis tracks vacancies and rents in the top 79 U.S. markets, and rents rose in 60 of them, led by Miami, Seattle and New York—all cities that have notched big rental declines in the past year.

Rents increased 1.6% in the first quarter in Miami and 0.9% in New York. The gains came during what is usually a seasonally weak period for apartments and suggested that landlords may have some momentum heading into the peak spring and summer leasing season.

"Deterioration seems not to have just been arrested but reversed," said Victor Calanog, director of research for Reis. "Several markets have bottomed and may be on track to recovery," he said.

Nationally, effective rents, which include concessions such as one month of free rent, rose 0.3% during the quarter compared with a 0.7% decline in the fourth quarter of last year and a 1.1% drop in the first quarter of 2009. Vacancies are tied to unemployment, because many would-be renters move in with family members or double up during a downturn.

"We clearly hit an inflection point in all of our markets in January and February," said Jeffrey Friedman, chief executive of Associated Estates Realty Corp., which owns and operates 12,000 units in the eastern U.S.

Renters are also staying put longer: the average renter now stays for 19 months, up from an average of 14 months, said Mr. Friedman, and despite low mortgage rates and greater home affordability, fewer renters are leaving to buy homes.

"This is the first time in many, many years that it feels like even people who could afford to buy are making the investment decision not to," Mr. Friedman said.

Difficulty in obtaining financing for new apartment construction, meanwhile, has limited the supply of new units that will be added in the coming years. Those fundamentals have landlords and investors excited about the potential for rents to pop once the economy gathers steam.

Still, Mr. Calanog said that a "slow recovery" was likely and that landlords shouldn't expect "galloping rental growth" until the job market firms up, particularly because younger workers that are more likely to rent have borne the brunt of job losses.

Others warned that gains were fragile and that landlords could continue to offer concessions to fill units.

"Rent reductions are not over yet," said Hessam Nadji, managing director at real-estate firm Marcus & Millichap. He said he didn't expect to see sustained rental growth until the second half of the year.

Barely half of the 22,000 units in buildings that opened their doors last quarter were filled, and landlords may cut deals because they face deadlines to pay back construction loans. "That's where renters are going to find deals," Mr. Calanog said.

The Reis numbers are for cities. The overall vacancy rate from the Census Bureau was at a near record 10.7% in Q4 2009.

Rents plunged in 2009 by the most in the 30 years Reis has been tracking rents - and with vacancies at record levels, the slight increase in Q1 2010 rents doesn't mean the rent declines are over.But why were there so many vacancies in the first place?

As discussed above, unemployment is causing people to double-up with others. And as the Wall Street Journal explained last October, there was overbuilding in some of the prime markets:

The housing bust has also flooded some of the most overbuilt housing markets with new apartment inventory as developers have converted unsold condominium developments into rentals.

![clip_image002[5] clip_image002[5]](http://www.creditwritedowns.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/10/clip_image0025_thumb.gif)

Just found this blog... its great. will be a daily reader and I believe there is a good chance I will be click in ads! excellent work.

ReplyDeleteHave you ever read Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations? If you even bothered to have read the first 100 pages, it would have explained right there, written 234 years ago, that the price of rent is based solely on a single factor-- the renters' ability to pay it. Period.

ReplyDeleteRental prices in the Washington, DC Metro region is holding up very well. The key factor is employment ... especially from the government.

ReplyDeleteGeez, the depth has outdone even much of your previous work. Just looked it over, and will need to contemplate. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteThe treatment of housing in the CPI is a many-splendored thing.

I don't follow the housing data as closely as I would like to, but one thing I'd like to look into if I did have the time, after reading this, is how well the futures prices on the Case-Schiller index did in anticipating current prices, or even themselves, in recent years. Can we trust what they say about the future today?

For that matter, that Case-Shiller chart was dated January 2010. Wonder what it looks like today?

ReplyDeleteFor that matter, that Case-Shiller chart was dated January 20101, wonder what it looks like today?

ReplyDeleteThis was a awesome blog. With all its statistics and all the detailed information, this blog becomes really awesome. I read your blog for the first time and now i am a big fan of your.

ReplyDelete