Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Arguments for Deflation: Unemployment, Debt and Deleveraging, the Pension Crisis, Collapse of the Shadow Banking System, and Interest on Reserves

As Absolute Return Partners wrote in its July newsletter:

The most important investment decision you will have to make this year and possibly for years to come is whether to structure your portfolio for deflation or inflation.

So which is it, inflation or deflation?

This is obviously a hot topic of debate, and experts weigh in on both sides. I’ve analyzed this issue in numerous posts, but every day there are new arguments one way or the other from some very smart people.

Because the arguments for inflation are so obvious and widely-discussed (bailouts, quantitative easing, Fed purchasing treasuries, etc.), I will not discuss them here (other than pointing to an interesting new argument for inflation by Andy Xie).

How Bad Could It Get?

The biggest deflation bears are rather pessimistic:

- David Rosenberg says that deflationary periods can last years before inflation kicks in

- Renowned economist Dr. Lacy Hunt says that we may have 15-20 years of deflation

- PhD economist Steve Keen says that – unless we reduce our debt – we could have a “never-ending depression”

These are the most pessimistic views I have run across. Most deflationists think that a deflationary period would last for a shorter period of time.

The Best Recent Arguments for Deflation

Following are some of the best arguments for deflation.

Unemployment

Wall Street Journal’s Scott Patterson writes that we won’t get inflation until unemployment is down below 5%:

A rule of thumb is that inflation doesn’t become sticky until the unemployment rate dips below 5%…

“I see very little prospect of accelerating inflation” partly because of the employment outlook, said Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Economy.com. “I don’t think the risk shifts toward inflation until 2011, or even 2012.”

It could take a lot longer for unemployment to go back down to 5% (and for consumers to have more money to spend again).

(Note: hyperinflation is obviously an entirely different animal. For example, there was rampant unemployment in the Weimar Republic during its bout with hyperinflation ).

Debt Overhang and Deleveraging

Steve Keen argues that the government’s attempts to increase lending won’t work, consumers will keep on deleveraging from their debt, and that – unless debt is slashed – the massive debt overhang will keep us in a deflationary environment for a long time.

Edward Harrison notes:

Nomura’s Chief Economist Richard Koo wrote a book last year called "The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics" which introduced the concept of a balance sheet recession, which explains economic behaviour in the United States during the Great Depression and Japan during its Lost Decade. He explains the factor connecting those two episodes was a consistent desire of economic agents (in this case, businesses) to reduce debt even in the face of massive monetary accommodation.

When debt levels are enormous, as they are right now in the United States, an economic downturn becomes existential for a great many forcing people to reduce debt. Recession lowers asset prices (think houses and shares) while the debt used to buy those assets remains. Because the debt levels are so high, suddenly everyone is over-indebted. Many are technically insolvent, their assets now worth less than their debts. And the three D’s come into play: a downturn leads to debt deflation, deleveraging, and ultimately depression. The D-Process is what truly separates depression from recession ...

See a presentation by Koo here.

Leading investment advisor Ray Dalio says the same thing.

Mish writes:

An over-leveraged economy is one prone to deflation and stagnant growth. This is evident in the path the Japanese took after their stock and real estate bubbles began to implode in 1989.

Leverage is increasing again, according to an article in Bloomberg:

Banks are increasing lending to buyers of high-yield company loans and mortgage bonds at what may be the fastest pace since the credit-market debacle began in 2007…

“I am surprised by how quickly the market has become receptive to leverage again,” said Bob Franz, the co-head of syndicated loans in New York at Credit Suisse…

Indeed, as I have repeatedly pointed out, Bernanke, Geithner, Summers and the chorus of mainstream economists have all acted as enablers for increasing leverage.

Mish continues:

Creative destruction in conjunction with global wage arbitrage, changing demographics, downsizing boomers fearing retirement, changing social attitudes towards debt in every economic age group, and massive debt leverage is an extremely powerful set of forces.

Bear in mind, that set of forces will not play out over days, weeks, or months. A Schumpeterian Depression will take years, perhaps even decades to play out.

Thus, deflation is an ongoing process, not a point in time event that can be staved off by massive interventions and Orwellian Proclamations “We Saved The World”.

Bernanke and the Fed do not understand these concepts, nor does anyone else chanting that pending hyperinflation or massive inflation is coming right around the corner, nor do those who think new stock market is off to new highs. In other words, almost everyone is oblivious to the true state of affairs.

Pension Crisis

Pension expert Leo Kolivakis writes:

The global pension crisis is highly deflationary and yet very few commentators are discussing this.

Collapse of the Shadow Banking System

Hoisington’s Second Quarter 2009 Outlook states:

One of the more common beliefs about the operation of the U.S. economy is that a massive increase in the Fed’s balance sheet will automatically lead to a quick and substantial rise in inflation. [However] An inflationary surge of this type must work either through the banking system or through non-bank institutions that act like banks which are often called “shadow banks”. The process toward inflation in both cases is a necessary increasing cycle of borrowing and lending. As of today, that private market mechanism has been acting as a brake on the normal functioning of the monetary engine.

For example, total commercial bank loans have declined over the past 1, 3, 6, and 9 month intervals. Also, recent readings on bank credit plus commercial paper have registered record rates of decline. The FDIC has closed a record 52 banks thus far this year, and numerous other banks are on life support. The “shadow banks” are in even worse shape. Over 300 mortgage entities have failed, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are in federal receivership. Foreclosures and delinquencies on mortgages are continuing to rise, indicating that the banks and their non-bank competitors face additional pressures to re-trench, not expand. Thus far in this unusual business cycle, excessive debt and falling asset prices have conspired to render the best efforts of the Fed impotent.

Ellen Brown argues that the break down in the securitized loan markets (especially CDOs) within the shadow banking system dwarfed other types of lending, and argues that the collapse of the securitized loan market means that deflation will – with certainty – continue to trump inflation unless conditions radically change.

Support for Brown’s argument comes from several sources.

As the Washington Times notes:

“Congress’ demand that banks fill in for collapsed securities markets poses a dilemma for the banks, not only because most do not have the capacity to ramp up to such large-scale lending quickly. The securitized loan markets provided an essential part of the machinery that enabled banks to lend in the first place. By selling most of their portfolios of mortgages, business and consumer loans to investors, banks in the past freed up money to make new loans. . . .“The market for pooled subprime loans, known as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), collapsed at the end of 2007 and, by most accounts, will never come back. Because of the surging defaults on subprime and other exotic mortgages, investors have shied away from buying the loans, forcing banks and Wall Street firms to hold them on their books and take the losses.”

Senior economic adviser for UBS Investment Bank, George Magnus, confirms:

The restoration of normal credit creation should not be expected, until the economy has adjusted to the disappearance of shadow bank credit, and until banks have created the capacity to resume lending to creditworthy borrowers. This is still about capital adequacy, where better signs of organic capital creation are welcome. More importantly now though, it is about poor asset quality, especially as defaults and loan losses rise into 2010 from already elevated levels.

And McClatchy writes:

The foundation of U.S. credit expansion for the past 20 years is in ruin. Since the 1980s, banks haven’t kept loans on their balance sheets; instead, they sold them into a secondary market, where they were pooled for sale to investors as securities. The process, called securitization, fueled a rapid expansion of credit to consumers and businesses. By passing their loans on to investors, banks were freed to lend more.

Today, securitization is all but dead. Investors have little appetite for risky securities. Few buyers want a security based on pools of mortgages, car loans, student loans and the like.

“The basis of revival of the system along the line of what previously existed doesn’t exist. The foundation that was supposed to be there for the revival (of the economy) . . . got washed away,” [economist James K.] Galbraith said.

Unless and until securitization rebounds, it will be hard for banks to resume robust lending because they’re stuck with loans on their books.

Fed Paying Interest on Reserves

And Naufal Sanaullah writes:

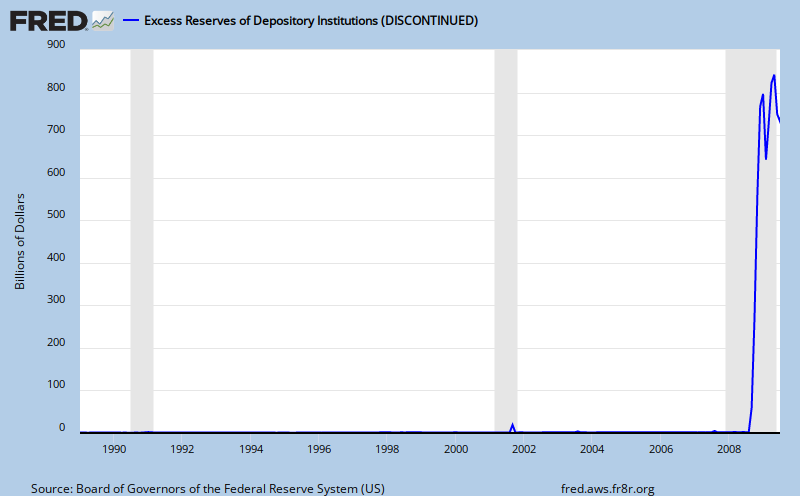

So if all of this printed money is being used by the Fed to purchase toxic assets, where is it going?

Excess reserves, of course. Counting for $833 billion of the Fed’s liabilities, the reserve balance with the fed has skyrocketed almost 9000% YoY. Excess reserves, balances not used to satisfy reserve requirements, total $733 billion, up over 38,000%!

The Fed pays interest on these reserves, and with an interest rate (return on capital) comes opportunity cost. Banks hoard the capital in their reserves, collecting a risk-free rate of return, instead of lending it out into the economy. But what happens as more loan losses occur and consumer spending grinds to a halt? The Fed will lower (or get rid of) this interest on reserves.

And that is when the excess liquidity synthesized by the Fed, the printed money, comes rushing in and inflates goods prices.

Of course, most people who are arguing we will have deflation for a while believe that we might eventually get inflation at some point in the future.

4 comments:

→ Thank you for contributing to the conversation by commenting. We try to read all of the comments (but don't always have the time).

→ If you write a long comment, please use paragraph breaks. Otherwise, no one will read it. Many people still won't read it, so shorter is usually better (but it's your choice).

→ The following types of comments will be deleted if we happen to see them:

-- Comments that criticize any class of people as a whole, especially when based on an attribute they don't have control over

-- Comments that explicitly call for violence

→ Because we do not read all of the comments, I am not responsible for any unlawful or distasteful comments.

quick comment regarding rising oil prices contributing to inflation, the so called bottleneck theory.

ReplyDeleteAs Andy Xie pointed out "Oil is essential for routine economic activities, and its reduced consumption has a large multiplier effect."

while oil prices may spike due to speculation re: anticipated inflation, & recent history has a good example, the bubble can quickly burst once economic activity (& corresponding consumption) declines quickly.

in this regard, I think oil prices will be somewhat self-regulating in that if they climb too high and/or too quickly, due more to expectation/speculation than real demand, they will act as a drag on a weakened economy and recede due to their impact on consumption.

High unemployment & overleveraged consumer will mean that manufacturer's will find it difficult to pass along cost increases due to higher oil prices, at least when it comes to discretionary goods/services. that will eat at their margins, forcing inefficient ones out of business.

A slow, gradual rise in prices would be more sustainable assuming increases in productivity that would enable manufacturer's to absorb such increased costs without adversely impacting profit margins.

the wild card is that much of the global supply of oil happens to be located in relatively small area which has a history of geopolitical turmoil flaring up from time to time...in some cases attributable primarily to oil supplies.

any geopolitical "shock" such as an attack on iran's nuclear facilities, or a terrorist attack on saudi arabia would render the deflation/inflation argument a moot point.

I live in a small town in northern Maine.

ReplyDeleteHere, -if you do not have a car, and a growing number do not have cars, -it is impossible to find work. It's impossible to find real work even with a car here.

I have literally seen people walking up to four and five miles one way -to try and hold onto a part-time minimum wage job -where the employer will have you show up for work, only to send you home -before you ever punch in. And he'll fire you -if you do not show up the next day for similar treatment.

Lots of people do not work at all.

I know this is so, because I see large numbers of people walking to the small local grocery store from miles away and back home with plastic sacks filled with food stretching each of their long arms.

Some walk a hundred yards, -some twenty yards. They put down their heavy loads. Rest a minute or two -rubbing their shoulders. And then they pick up their parcels again, and walk another hundred yards, or twenty, -depending on the stamina and health of the -shopper.

The stupendously-rigged oil inflation at $70 a barrel is already taking its toll on our economy.

This inflation is temporary though, because the whole economy here (and everywhere else too) is imploding due to massive damage to too many critical components.

It's an ugly and depressing Humpty-Dumpty world out there -full of scavengers and thieves, tattooed whores, skin-headed pimps, and drug-dealers who will always sell you something -at any price you can pay -but it's all laced with Strychnine, which is rat poison.

You see young adults here starting in their early twenties, having entirely given up, with their teeth half gone, methamphetamine-rotten, or just rotten, or beaten out of their head in a fist fight with their father or their fat girlfriend who loves them dearly despite their fall into abject poverty.

Everyone is trying -against all hope- to keep one step ahead of -no choice at all about doing with even less, or, spending some time in jail for thinking about pilfering someone's STUFF.

The biggest thing you can steal here that has any value is a chainsaw or a cow.

It's astonishing -what real poverty in America looks like if you're not prepared for it in advance.

Most of the cell phones -we used to see -are gone the same way the cars went.

You don't have to have a PHD to figure out we are seeing inflation in the markets... the entire rally has been fueled by a weaker dollar.

ReplyDeleteThe real problem is the one you state at the outset: inflation or deflation. In other words, the problem is that no one anymore knows what price to charge or pay or what wage to expect or to pay. The real problem is that we are well beyond the inflation vs. deflation point and into completely new territory. If you raise your price, then you will lose too many customers. And if you lower it or keep it the same, then you won't make any profit.

ReplyDeleteDo you see where this is going? Stop trying to reassure yourself with happy thoughts about the unlikelihood of inflation, because this is NOT Germany in the 20's. Nor is it the USA in the 30's. It is far far worse.

Or better.

If you can't either raise or lower prices or keep them the same then you are in the perfect state of uncertainty desired by every Zen novice. A whole new world opens up for you and anything is possible.

http://amoleintheground.blogspot.com/2009/02/gate.html