Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Peak Gold?

Gold bug Byron King claims that there is yet another reason that gold might be a reasonable investment: declining production.

In an interview yesterday, King argues:

Because we're in a world that appears to have encountered peak gold as well as peak oil. If you look at historical production, worldwide gold output reached a top right around the year 2000–2001. Overall output has declined and we're not replacing output from the big mines of the past. Despite discoveries here and there, miners have to dig deeper and deeper into the reserves. In a big mining country such as South Africa, for example, some of the deepest mines now are at 4,000 meters. That's 13,000 feet.

Is King right?

Yes, it turns out he might be.

Mining-Technology.com stated in March 2008:

Global gold production has been in steady decline since 2002. Production in 2007 was around 2,444t, down 1% on the previous year.

Analysts note that virtually all of the low-lying fruit has now been picked with respect to gold, meaning that companies will have to take on more challenging and more expensive projects to meet supply. The extent to which the current high price of gold can translate into profits remains to be seen...

According to Bhavesh Morar, national leader of the mining, energy and infrastructure group with Deloitte Australia, frenzied exploration activity over the last few years has seen virtually all of the easy harvest been picked with respect to gold...

The high price of gold is however encouraging more adventurous projects, be they more challenging financially, geologically, geopolitically or all three. New projects for gold and other resources are mushrooming throughout Africa, China, the Middle East and the former Soviet Union; all areas where sovereign risk is potentially very high.

Zeal Speculation and Investment wrote in July of this year:

Miners have the same geological landscape to work with today as those miners thousands of years ago. The only difference is the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. Gold producers must now search for and mine their gold in locations that may not be very amenable to mining. Many of today’s gold mines are located in parts of the world that would not have even been considered in the past based on geography, geology, and/or geopolitics.

And these factors among many are attributable to an alarming trend we are seeing in global mined production volume. According to data provided by the US Geological Survey, global gold production is at a 12-year low. And provocatively this downward trend has accelerated during a period where the price of gold is skyrocketing.

You would think that with the price of gold rising at such a torrid pace gold miners would ramp up production in order to profit from this trend. But as you can see in this chart this has not been the case, at all. Not only has gold production not responded, but it has dropped at an unsightly pace that has sent shockwaves throughout the gold trade.

As the red line illustrates gold’s secular bull began in 2001, finally changing direction after a long and brutal bear market drove down prices to ridiculous lows in the $200s. To match this bull the blue-shaded area provides a picture of the corresponding global production trend. And you’ll notice that in the first 3 years of gold’s bull production was steady. This is not a surprise as you figure it would take the producers a few years to ramp up supply. But instead of supply increasing in response to growing demand and rising prices, it took a turn to the downside. And what’s even more amazing is the persistence of this downtrend. Since 2001 gold production is down a staggering 9.3%! In 2008 there were 7.7m fewer ounces of gold produced than in 2001.

Also in July, Whiskey and Gunpowder posted a chart on historical gold production, and argued for decreasing production:

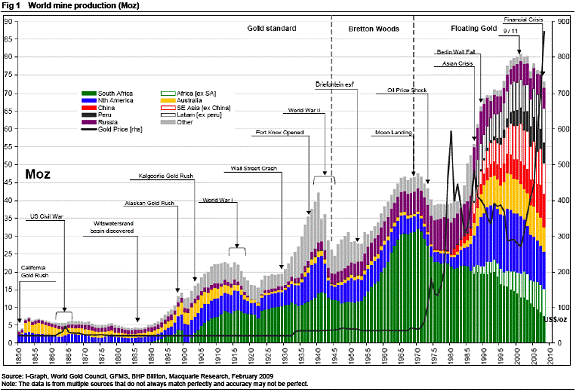

Take a look at the chart below from Macquarie Research, depicting world gold production 1850-2008...

[Click here for full chart]

For example, look at the very steep rise in gold output during the 1930s. That was during the depths of the worldwide Great Depression.

In both the US/Canada (blue area), and the rest of the world (gray area), people were digging more and more gold. The Soviets (purple area) increased their gold output too, courtesy of Joseph Stalin and his Gulag. Desperate times call for desperate measures, I suppose. Will that sort of history repeat this time around?

Or look at that massive run-up in gold output from South Africa (green area) in the 1950s and 1960s. That was during a time when South Africa was instituting its post-World War II system of apartheid. Labor was cheap (sorrowfully cheap), and quite a lot of international investment poured into South Africa without moral qualm. The South Africans dug deep and just plain tore into those gold-bearing reef structures of the Witwatersrand Basin.

But notice how quickly the South African gold output declined in the 1970s, as the mines got REALLY deep and the rest of the world began to institute sanctions against South Africa over its apartheid system.

And then look at the Gold Price run-up that followed in the late 1970s. It was a time of inflation, mainly coming from the US Dollar. Yet world gold mine output was dropping as well. Falling output, plus monetary inflation? The Gold Price skyrocketed. Another bit of useful history, right?

Now let's focus on more recent history, since about 1990. There were large increases in gold output from the US/Canada (blue), Australia (gold) and Asia (China orange, non-China open bar). By 2000 or so – the world production peak – Gold Prices were down toward $300 per ounce and below.

But as the chart shows, in the past 10 years, gold output has shown a marked DECLINE in the major historic Gold Mining regions. The prolific gold output from the US/Canada, Australia and South Africa has followed downward trends. Sure, these regions still lift a lot of ore and pour a lot of melt. But the production trend is DOWN.

The US/Canada, Australia and South Africa all have well-established and (more or less) workable mining laws – despite the best efforts of many current politicians and regulators to screw it all up. These historically producing areas are politically stable. Overall, there's good mining infrastructure, with road and rail networks, power systems, refining plants, a vendor base, mining personnel and access to capital.

But that's not the case in many areas of the developing parts of the world. Political stability? Security? Infrastructure? Transport? Power? Refining? Vendors? Personnel? Capital? Everywhere is different, of course. But overall, the entire process is much more problematic. So there's a lot more risk. When you move away from the traditional mining jurisdictions, the whole process of exploration, development and mining is more expensive.

Thus, the new gold discoveries of the future are going to lack some (if not most, or perhaps all) of the advantages of the developed mining world. That means that the ore deposits of the future will have to offer much higher profit margins, based on size and ore grade, to compensate for the increased risks. Too bad Mother Nature (or Saint Barbara, who looks after miners) doesn't work that way.

It also means the timeline to develop the mines of the future will likely be stretched over many years while political, legal, bureaucratic, logistical and social issues are ironed out.

The key driver for the future of worldwide gold supply will be DECLINING output overall over time.

Of course, if the price of gold warrant ramping up then production will increase. Just as with discussions about peak oil, the issue is not that the resource is totally running out, it is that it will be more and more expensive to extract.

I know that there have been warnings about peak oil since at least the 1970's. Top experts now say peak oil is real. See this, this and this. But I am not an expert on oil or gold.

Note: I am not an investment advisor and this should not be taken as investment advice.

Senior Moody's Executives: There's a Culture of Covering Up Improper Ratings

Reuters notes:

Two former Moody's executives, in testimony at a House Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing, said workers were encouraged to remain silent and cover up evidence of alleged improper practices in assigning and monitoring credit ratings.

The two "described a culture of secrecy, a place where putting things in writing was frowned upon," said Rep. Edolphus Towns, the Democratic chairman of the panel. "Can you imagine working at a place where the very act of writing a memo or sending an email is suspect?"...

Two former Moody's executives -- Scott McCleskey and Eric Kolchinsky -- testified that senior managers were willing to silence employees who raised concerns about the ratings process or compliance efforts.

McCleskey said that while he was the head of compliance at Moody's, he voiced concerns that the firm was not properly monitoring ratings on municipal debt. McCleskey, who was dismissed by Moody's in 2008, said he was instructed not to mention the issue in e-mails or writing.

Kolchinsky, a Moody's managing director who was recently suspended by the firm, said senior managers pushed revenue over ratings quality and were willing to fire employees who disagreed.

The congressional testimony can be read in full here.

Previously, I've pointed out that employees of the big 3 ratings agencies admitted that they had sold their soul for higher fees, that the rating agencies took "bribes" for higher ratings, and that Moody's argued in court that anyone who believed its ratings was an idiot.

The ratings companies also admitted that they didn't fire the analysts who gave AIG and Bear Stearns AA or higher ratings up until the moment they went bankrupt.

Reuters also notes:

Rep. Edolphus Towns, the Democratic chairman of the panel ... also said his committee would investigate why the Securities and Exchange Commission failed to act on a March 2009 letter sent by Moody's former senior vice president of compliance. The executive urged the SEC to take a closer look at Moody's weak compliance department and ratings process.

Credit Default Swaps - Love 'Em, Ban 'Em, or Tax 'Em?

I have repeatedly argued that over-the-counter credit default swaps (CDS) - or at least at least "naked" CDS - should be banned ("naked CDS" is the term I coined to describe the situation where the buyer is not the referenced entity. I will not comment on whether or not there is a real economic benefit when the referenced company buys CDS concerning itself or its suppliers as an insurance policy; I will leave that analysis to the CDS experts).

Says Who?

I'm in good company, of course, as many economists and financial advisors have warned of the dangers of CDS:

- A Nobel prize-winning economist (George Akerlof) predicted in 1993 that CDS would cause the next meltdown

- Warren Buffett called them “weapons of mass destruction” in 2003

- Warren Buffett’s sidekick Charles T. Munger, has called the CDS prohibition the best solution, and said “it isn’t as though the economic world didn’t function quite well without it, and it isn’t as though what has happened has been so wonderfully desirable that we should logically want more of it”

- Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan - after being one of their biggest cheerleaders - now says CDS are dangerous

- Former SEC chairman Christopher Cox said "The virtually unregulated over-the-counter market in credit-default swaps has played a significant role in the credit crisis''

- Newsweek called CDS "The Monster that Ate Wall Street"

- President Obama said in a June 17 speech on his plans for finance industry regulatory reform that credit swaps and other derivatives “have threatened the entire financial system”

- George Soros says the market is still unsafe, and that credit- default swaps are “toxic” and “a very dangerous derivative” because it’s easier and potentially more profitable for investors to bet against companies using them than through so-called short sales.

- U.S. Congresswoman Maxine Waters introduced a bill in July that tried to ban credit-default swaps because she said they permitted speculation responsible for bringing the financial system to its knees.

- Nobel prize-winning economist Myron Scholes - who developed much of the pricing structure used in CDS - said that existing over-the-counter CDS were so dangerous that they should be “blown up or burned”, and we should start fresh

- In perhaps the most anti-derivatives statement of all, Nassim Nicholas Taleb said this month, "To curb volatility in financial markets some financial products 'should not trade,' including complex derivatives."

But CDS seller are now saying everything is fine, that they are making changes which reduce risk, and that the danger has passed.

As an article in Bloomberg noted this week:

A year after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., credit-default swaps have lost their stigma for disaster.

So are CDS really safe now?

Not So Safe

Well, initially, before we can even begin to have an intelligent discussion about this issue, it is important to note that - according to Satyajit Das, a leading credit default swap expert - the commonly-accepted figures for the CDS losses suffered due to Lehman's bankruptcy have been understated. He also says that the justifications for the value of CDS for the economy are phony.

And it is also important to acknowledge that the government's proposed regulations of CDS (if they ever pass) won't really fix the problem. Indeed, Das says that the new credit default swap regulations not only won't help stabilize the economy, they might actually help to destabilize it.

And it should be remembered that the overwhelming majority of derivatives are held by just 5 banks. So the people behind the effort to reassure everyone that CDS are safe again are the too big to fail banks, desperate to restart the toxic asset and exotic instrument gravy train.

And the big financial firms and the government are both desperate to increase leverage, rather than allowing the deleveraging play out. See this, this, this, this and this.

As Nouriel Roubini said last month:

This is a crisis of solvency, not just liquidity, but true deleveraging has not begun yet because the losses of financial institutions have been socialised and put on government balance sheets. This limits the ability of banks to lend, households to spend and companies to invest...

The releveraging of the public sector through its build-up of large fiscal deficits risks crowding out a recovery in private sector spending.

CDS are an important way of creating leverage (for example, last year, the market for credit default swaps was larger than the entire world economy). So there is a huge (although wrong-headed, in my opinion) incentive to underplay the risks of CDS.

It is also possible to argue (although I haven't seen this argument validated by any experts) that CDS are inherently destabilizing for the financial system since they increase interconnectivity.

And don't forget that credit default swap counterparties drive company after company into bankruptcy, and that - once a company the counterparties are betting against goes bankrupt - the counterparties cut in line in front of all of the bankruptcy creditors to get paid (and see this and this). In other words, there are other problems caused by CDS other than destabilizing the economy as a whole.

Interesting Alternatives

Two of the most interesting proposals in dealing with CDS come from Paul Volcker and Yves Smith.

Volcker argues that banks which receive taxpayer bailouts should not be heavily exposed to derivatives trading.

Yves Smith says that the best approach would be to significantly tax credit default swaps. She argues that that would shrink the CDS market - and the associated risks - faster than anything else. The more I think about it, the more Smith's approach makes sense.

The Bigger Problem

Perhaps most importantly, CDS sellers - like the big sellers of other financial products - know that the government will bail them out if CDS crash again. So they have strong incentives to sell them and to recreate huge levels of leverage.

Indeed, the same dynamic that led to the S&L crisis also led to last year's CDS crisis, and will lead to the next crisis as well. So - while CDS might be a particularly dangerous type of "weapon of mass destruction" (in Buffet's words) - the financial looters will probably find some way to loot on the public's dime, no matter what happens to CDS, unless they are they are meaningfully reigned in (or broken up).

In other words, the bottom line is that - yes - CDS are still dangerous. But - just as a killer, unless restrained, could use a paper weight to kill - the too-big-to-fails would just use some other instrument even if naked over-the-counter CDS are banned or tamed. Taking away a convicted murderer's gun might be a good first step. But if he is still free to cause harm, he may very well kill again.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Simon Johnson: "Barack Obama, Like Louis XIV Before Him, Knows Exactly What is Going On"

Many people assume that Obama doesn't understand that his economic team - Summers, Geithner, Bernanke, Gensler and the boys - are preserving the status quo, and failing to make the fundamental reforms needed to stabilize the economy.

They assume that the economy is a mysterious subject for experts, and that Obama innocently thinks his team is doing good for the American people.

But professor of economics and former chief IMF economist Simon Johnson isn't buying it.

As Johnson and James Kwak write today in the Washington Post:

During the reign of Louis XIV, when the common people complained of some oppressive government policy, they would say, "If only the king knew . . . ." Occasionally people will make similar statements about Barack Obama, blaming the policies they don't like on his lieutenants.If Obama doesn't institute fundamental reforms now, Simon will blame him - and not just his advisors or the the lobbyists.

But Barack Obama, like Louis XIV before him, knows exactly what is going on.

Is Gold A Reasonable Investment?

This essay rounds up arguments for gold as a reasonable investment.

China

Commentators such as Ambrose Evans-Pritchard and Byron King argue that China's hunger for gold will put a floor on gold prices.

Specifically, they argue that China will "buy the dips" in gold prices, effectively putting a minimum on how low gold prices can go.

Inflation

It is conventional wisdom that gold is a hedge against inflation.

For example, noted inflationist John Williams advises buying gold.

Axel Merk argues that gold is a better buy than TIPS as an inflation bet.

And Taleb advised buying gold in May, since currencies including the dollar and euro face pressures.

Deflation

If gold does well during times of inflation, it makes sense that it would perform poorly during deflationary periods.

But Examiner.com points out that such an assumption is probably untrue.

Specifically, as Examiner.com writes:Eric Sprott - who manages $4.5 billion in assets, and correctly predicted in March of 2008 a "systemic financial meltdown” - says:“I believe no matter what environment you’re in - deflation or inflation - people will run to gold,” Sprott said. “Gold is proving exactly what we all would have expected, that in almost any environment, it’s a go-to asset.”And investment analyst and financial writer Yves Smith argues that gold does well during both periods of deflation and high inflation. She argues:

Historically, gold does well [in] hyperinflation and deflationary [periods]. Gold does poorly under more normal conditions, and gets hammered in disinflationary conditions, a falling but positive rate of inflation.

Analyst Adrian Ash argues that gold's value actually increases during periods of deflation even if its price drops:

Does the price of gold rise or fall in a deflation?Hint: It’s a trick question, already tripping up plenty of would-be advisors...

Absent the money-supply limits which the gold standard imposed on the world, people rightly guess that double-digit inflation would prove rocket-fuel for the bull market in gold. Yet the purchasing power of gold nearly doubled during the Great Depression, and it’s risen four-fold during this decade’s low consumer-price inflation as well.Why? Because both those periods of low price-inflation saw the money-issuing authorities devalue the currency, first with explicit reference to gold but now without daring to name it. Roosevelt in the mid-30s slashed the dollar’s gold content by 40%; the Greenspan/Bernanke Fed devalued the Dollar again to sidestep a DotCom Depression, keeping real interest rates at less than zero, between 2002-2005.

The maestro’s apprentice applied the same trick in the back-half of 2008, but so far to no avail. And now even the European Central Bank is pumping out money – a near half-trillion euros today alone – in a bid to revive bank lending, swamp the currency markets, and pull Germany out of its first flirt with deflation since the 1930s.

Just such a devaluation – and again, absent any stated reference to gold – was attempted by the Bank of Japan a little less than a decade ago.

Indeed, Japan is the only developed nation since the end of the gold standard to have suffered an extended deflation in prices. So far, at least. Germany and Switzerland look set to try for a re-wind, and unless the dollar can outpace the euro’s descent, we might yet see truly sub-zero inflation in the United States, too.

But whatever that should mean for gold prices, all other things being equal, just doesn’t matter. Because the gold price will not get a chance. All other things are not equal, and the policy solution – rank devaluation – can only make gold more appealing to investors and savers, whether the “monetarist experiment” of TARP, quantitative easing or a half-trillion euros proves successful or not.

Japan’s slump into deflation coincided with the Bank of Japan’s “zero interest rate policy” (ZIRP) at the start of this decade. It also saw the gold price worldwide hit rock-bottom and turn higher, a move that analysts (including us) have typically linked to US monetary moves and investment cash looking for safety as the Dotcom Bubble exploded.

But zero-rate money from the world’s second-largest economy shouldn’t be ignored. And today, zero-rate money is all the developed world has to offer – a trick that might not beat deflation, but might just spur a whole new rush into gold.

In other words, Ash argues that you can't take inflation or deflation in a vacuum. During deflationary periods - like we have now - governments always increase the money supply with a flood of new dollars, which is bullish for gold.

And PhD economist Marc Faber wrote in October 2007 that gold will do well even in a deflation:

How would gold perform in a deflationary global recession? Initially gold could come under some pressure as well but once the realization sinks in how messy deflation would be for over-indebted countries and households, its price would likely soar.

Therefore, under both scenarios - stagflation or deflationary recession - gold, gold equities and other precious metals should continue to perform better than financial assets.Looking At the Charts

Is Faber right?

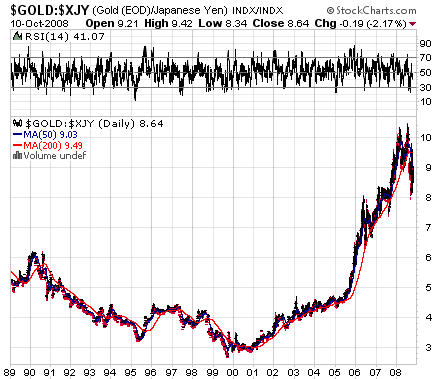

Well, take a look at the following charts showing gold's performance as compared to the yen during Japan's "lost decade" of deflation:

Japan's deflation didn't definitively end until 2007 or 2008.

This provides some evidence that gold may tend to hold or increase its value at least in the later part of the deflationary period as compared with the relevant national currency.

Moreover - approximately half the time - gold has risen during recessions in the United States:

(The grey vertical bars show periods of recession; the chart gives gold prices in monthly averages; click here for larger image).

If you study the above chart, you will see that gold seems to often fall during the beginning stages of a recession, then rise in the later stages of the recession (before 1971, the dollar was still backed by gold at a fixed price, and so gold did not fluctuate).

But what about Ash's theory?

The American Enterprises Institute notes:

After five years in a deflationary economic wilderness, the Bank of Japan switched during the spring of 2001 to a policy of quantitative easing--targeting the growth of the money supply instead of nominal interest rates--in order to engineer a rebound in demand growth.Look again at the first gold chart for Japan, above. Gold appears to start increasing against the Yen in 2001.

This may provide some evidence for Ash's thesis that it is an expansion of the money supply which pushes the price of gold up in the later stages of deflationary periods.

Uncertainty

Finally, Chris Martenson argues that - in prolonged periods of deflation - we usually see failures of large and significant banks, institutions, and perhaps even states and countries. Because gold traditionally does well during periods of uncertainty, Martenson likes gold during periods of deflation.

Examiner.com notes in a subsequent article:

Global Short Term Interest Rates Are LowMerrill Lynch agrees.

Specifically, PhD economist Nouriel Roubini paraphrases a report from Merill Lynch (not available online) as follows:

Short-term rates of 0% are bullish for gold, which serves as a store of value but is a useful hedge against deflation as well, since deflation is inherently destabilizing for financial assets. In the 2001-03 deflationary period, gold rose more than 30%, not to mention the prospect of a return to a dollar bear market. "Gold is inversely correlated to global short-term interest rates and there is a race right now towards 0%. Production is down 4.0% y/y while fiat currencies globally are being created at a double digit rate by the world's central banks....As for all the talk of a 'gold bubble,' it would take a nearly 625% surge in gold to over US$6,000/oz and a flat stock market to actually get the ratio of the two asset classes back to where it was three decades ago when bullion was in an unsustainable bubble phase."

Gold tends to be less sensitive to global economic slowdown than industrial metals or energy and works better as a hedge against crisis than inflation.

The above-quoted Merrill article states:

Gold is inversely correlated to global short-term interest rates and there is a race right now towards 0%.This argues for gold.

Polls Show Distrust in Government

Time Magazine writes:

Traditionally, gold has been a store of value when citizens do not trust their government politically or economically.

Given the enormous levels of distrust in the government politically and/or economically (and the fact that some have warned of recession-induced violence), gold might do well.

Greenspan and Exeter

Professor Emeritus of Mathematics Antal Fekete has argued for years that gold is the ultimate - and only - safe haven when things really hit the fan.

For example, in 2007 Fekete wrote:

The grand old man of the New York Federal Reserve bank’s gold department, the last Mohican, John Exter explained the devolution of money (not his term) using the model of an inverted pyramid, delicately balanced on its apex at the bottom consisting of pure gold. The pyramid has many other layers of asset classes graded according to safety, from the safest and least prolific at bottom to the least safe and most prolific asset layer, electronic dollar credits on top. (When Exter developed his model, electronic dollars had not yet existed; he talked about FR deposits.) In between you find, in decreasing order of safety, as you pass from the lower to the higher layer: silver, FR notes, T-bills, T-bonds, agency paper, other loans and liabilities denominated in dollars. In times of financial crisis people scramble downwards in the pyramid trying to get to the next and nearest safer and less prolific layer underneath. But down there the pyramid gets narrower. There is not enough of the safer and less prolific kind of assets to accommodate all who want to "devolve”. Devolution is also called "flight toDarryl Schoon makes the same argument.

safety”.

Here's a visual depiction Exeter's inverted pyramid, courtesy of FOFOA:

(Click here for full image; I am not certain every level of the pyramid is accurately ranked)

Alan Greenspan has just lent some support to the theory. Specifically:

Gold prices that jumped above $1,000 an ounce this week are signaling that investors are buying metals to hedge against declines in currencies, former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said.

The gains are “strictly a monetary phenomenon,” Greenspan said today at an investment conference in New York. Rising prices of precious metals and other commodities are “an indication of a very early stage of an endeavor to move away from paper currencies,” he said...

“What is fascinating is the extent to which gold still holds reign over the financial system as the ultimate source of payment,” Greenspan said.

In other words, Greenspan is saying that investors are moving out of the second-to-lowest step on the pyramid (currencies and government bonds) and into the lowest step (gold).

Are Exeter, Fekete and Schoon right? I don't know. And Greenspan might be wrong, or trying to excuse weakness in the dollar (as opposed to all paper currencies).

Note 1: Zero Hedge alleges that newly-declassified federal documents prove that gold prices have been manipulated for decades. If these documents are authentic (I have no reason to doubt their authenticity, but have no inside knowledge), if the claims of artificial price suppression are true, if this is widely publicized, if such publicity causes someone like Congressmen Alan Grayson, Brad Sherman, Ron Paul, or Dennis Kucinich to raise a ruckus in Congress, and if Congress as a whole votes to ban such a practice, then the price of gold would presumably rise. That's a lot of ifs.

Note 2: Some of the best recent arguments I've heard against investing in gold are written by Vitaliy Katsenelson. Read this, this, this and this.

Note 3: I am not an investment advisor and this should not be taken as investment advice.

Derivatives Are Inherently Destabilizing for the Financial System Because they Increase Interconnectivity

Many smart people have said that credit default swaps destabilize the financial system. See this and this.

But there is yet another reason - one perhaps even more fundamental - why CDS are inherently destabilizing to our economy.

Remember, one of the reasons that AIG, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and Bank of America have been labeled "too big to fail" is that they are highly interconnected. In other words, mainstream economists believe that their interconnectivity means that a failure of any one of them could bring down the whole system.

For example, Paul Volcker told Congress last week that the approach proposed by the Treasury is to designate in advance financial institutions "whose size, leverage, and interconnection could pose a threat to financial stability if it failed."

Systems expert Valdis Krebs points out (as does Frontline) that the higher the interconnectivity of financial institutions, the more vulnerable the financial system.

Stephen G. Cecchetti - Economic Adviser and Head of the Monetary and Economic Department for the Bank for International Settlements - agrees that interconnectivity is one of the factors which leads to financial instability.

And as the New York Times pointed out earlier this month, derivatives increase the interconnectivity of banks:

Derivatives drove the boom before 2008 by encouraging banks to make loans without adequate reserves. They also worsened the panic last fall because they inherently tie institutions together. Investors worried that the collapse of one bank would lead to big losses at others.CDS tie the financial giants together with each other, with smaller banks, with other types of financial institutions, and with national, state and local governments. They therefore inherently destabilize the financial system.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Taleb: "Complex Derivatives ... Should Not Trade"

According to Bloomberg, Nassim Nicholas Taleb said today:

To curb volatility in financial markets some financial products “should not trade,” including complex derivatives ... While products such as options are acceptable, he still doesn’t understand some derivatives after 21 years in the industry.Taleb joins George Soros and many others who have called for banning credit default swaps.

Paul Volcker and others have said that banks which receive taxpayer bailouts should not be heavily exposed to derivatives trading.

But Yves Smith says that the best approach would be to tax credit default swaps. She argues that that would shrink the CDS market - and the associated risks - faster than anything else.

President of the World Bank Slams the Fed (and Other Central Banks) For Embracing Bubbles and Then Trying to Clean Up the Mess Once They Burst

World Bank President Robert Zoellick says:

Central banks [including the Fed] failed to address risks building in the new economy. They seemingly mastered product price inflation in the 1980s, but most decided that asset price bubbles were difficult to identify and to restrain with monetary policy. They argued that damage to the 'real economy' of jobs, production, savings, and consumption could be contained once bubbles burst, through aggressive easing of interest rates. They turned out to be wrong.This is in line with criticism of the Fed of BIS and many independent economists and financial experts.

The Case for Inflation

As I have recently pointed out, there are strong arguments for ongoing deflation.

But even deflationists think that - after a period of deflation - we might eventually get inflation. For example, in October, I guessed 1 1/2 to 2 years of deflation, followed by inflation.

Moreover, noted deflationist Martin Weiss - after predicting for 27 years straight that we'll have deflation - has now changed his mind, and thinks inflation is a greater short-term threat than deflation.

For these two reasons - and to make clear that the inflation versus deflation debate is complicated and includes many factors - this essay will focus on the arguments for inflation.

Faber and the Dollar

PhD economist Marc Faber said in May:

“I am 100% sure that the U.S. will go into hyperinflation.”

Faber said he thinks - in the medium-term - we could have high levels of inflation (and see this and this).

Faber's argument is that a weakening dollar will lead to inflation (as every dollar will buy less goods and services).

Government Printing

The government has injected trillions of dollars into the economy in the form of TARP bailout funds and other programs. Indeed, the government’s own watchdog over the TARP program - the special inspector general - said that number could be $23 trillion dollars in a worst-case scenario.

The basic argument for inflation is - as everyone knows - that the government has injected so much money into the economy (through bailouts, quantitative easing, purchase of treasuries, etc.) that there will be a lot more dollars chasing the same number of goods and services, which will drive up prices. In other words, the supply is the same, but demand has increased.

Indeed, the U.S. has also provided huge sums of dollars to foreign central banks. Could dollars given abroad cause inflation inside the U.S.? Yes - because some proportion of those dollars will be spent by citizens in those countries to buy stocks, commodities, goods and services within the U.S.

Three well-known advocates of the inflation argument are Rogers, Buffet and Schiff.

Specifically, billionaire investor Jim Rogers said we are facing an "inflationary holocaust".

Warren Buffett said:

The policies that government will follow in its efforts to alleviate the current crisis will probably prove inflationary and therefore accelerate declines in the real value of cash accounts.

And Peter Schiff has argued for years that hyperinflation will wipe out the value of the dollar, so people should get all of their money out of dollars and into foreign currencies and assets.

But is all this government printing and quantitative easing really enough to cause inflation?

The back-of-the-envelope figures I've seen bandied about say no. Because of the massive destruction of credit (which - as Mish has repeatedly pointed out - must be included in discussions of inflation versus deflation), the government would probably have to print one-and-a-half to two times as much as it already has in order to create inflation.

The government could still do so. Yes, it would be suicidal for the dollar and might cause foreign buyers of U.S. treasuries to stop buying, but the boys in Washington could - if they were crazy enough - increase the money printing and quantitative easing to the point where inflation actually kicks in.

Will they do so? Summers, Geithner and Bernanke have proven themselves willing to do a lot of crazy things over the past year, so I wouldn't rule the possibility out altogether.

Indeed, when the Option Arm, Alt-A and commercial real estate mortgages start defaulting in earnest, there will be a lot of pressure on Washington to "do something". But again, doubling the amount of money printing would turn the dollar into monopoly money, and so there will be a lot of pressure not to turn America into Zimbabwe.

Devaluing the Dollar

Many commentators also argue that the U.S. is intentionally devaluing the dollar in order to increase trade.

And - as everyone knows - the dollar might tank even if the boys don't intentionally devalue it into oblivion. Just look at the amount of printing and easing which has already been done, the tidal wave of debt overhang, and the lack of fundamental soundness in the giant banks, the financial system, and the U.S. economy as a whole.

Moreover, some people argue that the dollar carry trade will drive inflation. Specifically, they argue that we'll get "spec-flation", meaning that investors will buy dollars and - in a carry trade - use the dollars to invest abroad. This will devalue the dollar, creating inflation.

And, importantly, the U.S. is quickly losing its status as the world's reserve currency. Therefore, the "premium" on the value of the dollar for its status as reserve currency will also fade, and the value of the dollar decline.

For these and other reasons, Faber and other inflationists would argue that the dollar will continue to substantially decline and inflation will therefore kick in (Note: Mish is still a dollar bull, and so doesn't concede this point).

Unemployment

I have previously argued that the rising tide of unemployment will contribute to deflation for some time.

However, Edmond Phelps - who won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2006 - and PIMCO Chief Executive Officer Mohamed El-Erian both say that the "natural unemployment rate" has risen from 5 to perhaps 7 percent.

What is the natural unemployment rate? It just means that if unemployment falls below that a certain percentage, then inflation will be created.

So if the natural unemployment rate has risen, that may mean that we will get inflation sooner (when unemployment falls to 7%, instead of when it falls all the way back to the previous peg of 5%).

End of Foreign Bond Purchases?

Tiger Management founder and chairman Julian Robertson warns that - if foreign purchasers stop buying U.S. treasury bonds - inflation will strike:

If the Chinese and Japanese stop buying our bonds, we could easily see [inflation] go to 15 to 20 percent,” he said. “It's not a question of the economy. It's a question of who will lend us the money if they don't. Imagine us getting ourselves in a situation where we're totally dependent on those two countries. It's crazy.

Bottleneck Inflation

Finally, Andy Xie argues that "bottlenecks" can cause inflation. Specifically, Xie argues that inflation in a single key market - say oil - can cause inflation, even in a weak economy.

Conclusion

As I have argued for a year, we will probably have a period of deflation followed by inflation. I still believe that.

When inflation will kick in is the million dollar question. The inflation camp argues that inflation will kick in any second now without any warning. In the deflation camp, David Rosenberg argues for years of deflation, and Dr. Lacy Hunt argues for decades of deflation.

Bottom line: In my opinion, the question is when, not if.

But in investing, being too early is being wrong. Someone who is positioned for inflation decades too early will get creamed. Likewise, someone who is betting on deflation for 20 years will get hurt if inflation kicks in next month.

Note: Remember that we could also get mixed-flation. In other words, inflation in some asset classes and deflation in others. Indeed, given that speculators drove up the price of oil last year, it is possible that - especially in a stagnant economy - speculators could drive up the prices of some asset classes and drive others down.

Ron Paul Introduced Audit the Fed Bill in 1983 - Both Parties Blocked It for More Than 25 Years

The House Committee on Financial Services has just posted the video of Barney Frank's opening statement on the bill to audit the fed (HR 1207).

Frank provided some very interesting history in his opening statement.

Specifically, Frank says that Ron Paul originally introduced the bill for the first time in 1983. But for 12 years after that, the Republicans used their control of the Finance Committee to insure that there was "no time" to give Paul's bill a hearing.

In 2003, when Paul was in line to become chair of the domestic monetary subcommittee, that subcommittee - coincidentally enough - immediately disappeared, and was merged into another subcommittee in order to shield the Federal Reserve from the imminent oversight which a monetary subcommittee under Paul would presumably create.

Watch the video.

Update: A congressional aid just me with provided the following transcript of Frank's opening statement:

This is an historic hearing. The Gentleman from Texas, Mr. Paul, filed this bill for the first time in 1983. There then ensued a number of things including 12 years in which the Republican Party controlled the agenda of this committee and found no time for this hearing. So I am very pleased, in this show of bipartisanship, to have been the one to have given this important piece of legislation its first hearing ever. Indeed, and I think this history is relevant, because we (mumbles at 0:38) partisan issue. The first time this committee, in my experience – having come here in 1981, engaged with the Federal Reserve, and I think it was true of the ‘70s and ‘60s as well, but the first time this committee dealt with the questions of openness and transparency of the Federal Reserve was under the leadership of the great chairman who is pictured over my right shoulder – Henry B. Gonzalez. In fact, a former chief economist of this committee, Robert Auerbach, has written a book, and I get no share of the proceeds, but it was: [Something] and Deception at the Fed. It was a description of the efforts by Mr. Gonzalez, ultimately successful, to compel the Federal Reserve to be more open. It’s astonishing to me to remember that when I first came here the decisions of the Open Market Committee were never announced. Now, how you influence interest rates by concealing from the market what you decide to do is very odd. What it shows is that the penchant for secrecy outweighed the desire to be effective; because it clearly could not have been as effective to have a secret directive to the markets, which of course got leaked and distorted, etc.

There were minutes that had been taken at the Federal Reserve meetings. The Federal Reserve at the time – 1983, denied in the later 80s when Mr. Gonzalez became chairman, they denied that there had been minutes. They were later ‘found in a drawer.’ There were not reports released. So this is not a new thing for this committee. There was an effort to open it up and there was significant increased opening. The other point that is relevant, and I do want to say to make sure that this is not a partisan issue, is [facts on the record] in 2003 the gentleman from Texas, Mr. Paul was in line in seniority to be chairman of the Domestic Monetary Policy Subcommittee. That subcommittee immediately disappeared. It was merged into the International Monetary Policy Subcommittee because there were people who were trying to shield the Federal Reserve from Mr. Paul’s influence. Two years later, when they could not merge that subcommittee further into the Housing Subcommittee (although they probably thought about it), a member of this committee, with some seniority, who had not previously taken the subcommittee chairmanship - Congressman was persuaded to come over and do this. So this is the first time this bill was filed, and despite a bipartisan ignoring of the issue, and this is the first time that we have had had the hearing and we are serious about some legislation in this regard.

I will say that I have a couple of concerns. The Federal Reserve engages in considerable market activity – they buy and sell. I do believe that it is important to note, that in our society that that be made public. We don’t want public entities buying and selling securities with nobody else ever knowing. I also believe, however, that there needs to be some time to elapse so that their buying and selling does not have a direct market effect. [Some time so] that other people can’t ride on it. So that’s one area where I will be working with the gentleman from Texas, and we’ve discussed it. We want there to be publicity, we don’t want there to be a market effect in the near term. We don’t want people trading with the Fed or against the Fed, etc. As to monetary policy: I think it’s also clear that we don’t want…I believe, and have exercised that right for some time, to comment on monetary policy…the notion that no elected official should ever comment on something so important as monetary policy is profoundly anti-democratic. I believe that we should continue to do that, and that’s something I’ve been doing since I got here. We don’t want to give the rest of the world, or more importantly, domestic investors the impression that we are somehow, in a formal way, injecting Congress into the setting of monetary policy. Because I think that could have a very destabilizing effect. I don’t think that will be hard to do without in any other way interfering with other functions. But, how the Federal Reserve carries out what it is doing, its buying and selling (what it buys and sells), all those, given its importance, can entirely and legitimately be made open.And I will say this – there were predictions. One of the things that the media fails to do…the media rarely passes up a chance to refute those of us who are in office, but they get bored too easily. There are often predictions of doom whenever people in Congress propose to do something. Very often those predictions of doom go unrealized and there is too little checking. I urge people, if you are interested in this, go back to some of the predictions that were made in the late 80s, when under the leadership of Henry Gonzalez…when the Fed was not being legislated but pressured to make some changes, read about the predictions of doom and note that none of them came to pass. I believe that we are similarly able in a wholly responsible way, without in any way be interfering in the independence of the monetary policy setting function or with the integrity of the markets, to go forward with completing the job. And, I would say, completing the job that really did begin with Henry Gonzalez – but completing it, and a lot needs to be done. The gentleman from Texas has been in the lead in pushing for that. [He has been] making sure that this important part of our federal government is subjected to the same rules of openness that every other element in a democratic government should be.

Sunday, September 27, 2009

How Well Has The Federal Reserve Performed for America?

How well has the Federal Reserve performed for America? Mainstream pundits, of course, say that Bernanke has saved the world . . . . but they said the same thing about Greenspan. So let's look at the actual historical record to determine how well the Fed has done.

Initially, Milton Friedman and Ben Bernanke have both said that the Federal Reserve caused (or at least failed to cure) the Great Depression through its poor monetary policy.

Many also blame the Fed for blowing an unsustainable bubble between 2001-2007 through artificially low interest rates. If this sounds too much like an Austrian economics perspective, that may be true. But remember that Hayek won the Nobel prize in 1974 partly for arguing that artificially low interest rates lead to the misallocation of capital and to bubbles, which in turn lead to busts.

Moreover, one of the Fed's main justification has been that it can provide a "counter-cyclical" balance. In other words, during boom times it can put on the brakes ("take the punch bowl away right as the party gets started"), and during busts it can get things moving again. But as economist Jane D'Arista has shown, the Fed has failed miserably at that task:

The Fed is also supposed to act as a regulator for banks and their affiliates, but failed miserably in that role as well.Jane D'Arista, a reform-minded economist and retired professor with a deep conceptual understanding of money and credit [has a] devastating critique of the central bank. The Federal Reserve, she explains, has failed in its most essential function: to serve as the balance wheel that keeps economic cycles from going too far. It is supposed to be a moderating force in American capitalism on the upside and on the downside, the role popularly described as "leaning against the wind." By applying its leverage on the available supply of credit, the Fed can slow down a boom that is dangerously overwrought or, likewise, stimulate the economy if it is sinking into recession. The Fed's job, a former chairman once joked, is "to take away the punch bowl just when the party gets going." Economists know this function as "counter-cyclical policy."

The Fed not only lost control, D'Arista asserts, but its policy actions have unintentionally become "pro-cyclical"--encouraging financial excesses instead of countering the extremes. "The pattern that has developed over the last two decades," she wrote in 2008, "suggests that relying on changes in interest rates as the primary tool of monetary policy can set off pro-cyclical foreign capital flows that tend to reverse the intended result of the action taken. As a result, monetary policy can no longer reliably perform its counter-cyclical function--its raison d'être--and its attempts to do so may exacerbate instability."...

Indeed, the central bankers' central banker - BIS - has itself slammed the Fed:

The head of the World Bank also says:In a pointed attack on the US Federal Reserve, [BIS and its chief economist William White] said central banks would not find it easy to "clean up" once property bubbles have burst...

Nor does it exonerate the watchdogs. "How could such a huge shadow banking system emerge without provoking clear statements of official concern?"

"The fundamental cause of today's emerging problems was excessive and imprudent credit growth over a long period. Policy interest rates in the advanced industrial countries have been unusually low," [White] said.

The Fed and fellow central banks instinctively cut rates lower with each cycle to avoid facing the pain. The effect has been to put off the day of reckoning...

"Should governments feel it necessary to take direct actions to alleviate debt burdens, it is crucial that they understand one thing beforehand. If asset prices are unrealistically high, they must fall. If savings rates are unrealistically low, they must rise. If debts cannot be serviced, they must be written off.

"To deny this through the use of gimmicks and palliatives will only make things worse in the end," he said.

Central banks [including the Fed] failed to address risks building in the new economy. They seemingly mastered product price inflation in the 1980s, but most decided that asset price bubbles were difficult to identify and to restrain with monetary policy. They argued that damage to the 'real economy' of jobs, production, savings, and consumption could be contained once bubbles burst, through aggressive easing of interest rates. They turned out to be wrong.As PhD economist Steve Keen has pointed out, the Fed (along with Treasury) has also given money to the wrong people to kick-start the economy.

Remember also that Greenspan acted as one of the main supporters of derivatives (including credit default swaps) between the late 1990's and the present (and see this).

Greenspan was also one of the main cheerleaders for subprime loans (and see this).

The above list is only partial. And it ignores:

(1) allegations that the Fed has manipulated the markets; and

(2) claims that the Federal Reserve System saddles the U.S. government and American people with trillions of dollars in unnecessary debt (that would not be incurred if the government took back the "power to coin money" granted to the government itself in the Constitution).Even so, it shows that the Federal Reserve has performed very poorly indeed.

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Elliot Wave: Faber Versus Mish and McHugh

I am agnostic about Elliot Wave stock charting.

But, as I see it, there are two basic views of those who follow Elliot Wave.

On the one hand, Mish and McHugh think we might be on the verge of a major wave c down crash.

What does this mean?

Basically, a second major leg down in the stock market, just like the second leg down of the Great Depression.

On the other hand, in various recent interviews, Marc Faber - who also follows Elliot Wave - believes that (with some corrections along the way) the market will go up for the next 3-4 years. He then believes the entire capitalist system will crash, but that's another story.

So will we get a major wave C down crash in the near future, like Mish and McHugh think will probably happen?

In 3-4 years, as Faber thinks will happen?

Or not at all?

I don't know. But I think the spectrum of opinion from smart people is fascinating.

Friday, September 25, 2009

Why Consolidation in the Banking Industry Threatens Our Economy

As everyone knows, the big banks have gotten bigger and bigger. Noted economist Mark Zandi says we have an oligopoly of banks, and that "the oligopoly has tightened".

The TARP Inspector - Neil Barofsky - told Huffington Post yesterday that, because of the consolidation in the banking industry and the moral hazard created by the bailouts:

I think we may be in a far more dangerous place today than we were a year ago.

Why Consolidation is Dangerous

Economists and other financial experts could provide many reasons why concentration is dangerous. Certainly, their very size distorts the markets and limits the growth of smaller banks. and the economy cannot fundamentally recover while the giants continue to drag our economy down the drain.

But I would like to use an analogy from science to discuss why our current, highly-concentrated banking lineup presents a huge threat to our economy (analogies can sometimes be useful; e.g. Taleb talks about black swans).

It has been accepted science for decades that when all the farmers in a certain region grow the same strain of the same crop - called "monoculture" - the crops become much more susceptible.

Why?

Because any bug (insect or germ) which happens to like that particular strain could take out the whole crop on pretty much all of the region's farms.

For example, one type of grasshopper - called "differential grasshoppers" - loves corn. If everyone grows the same strain of corn in a town in the midwest, and differential grasshoppers are anywhere nearby, they may come and wipe out the entire town's crops (that's why monoculture crops require such high levels of pesticides).

On the other hand, if farmers grow a lot of different types of crops ("polyculture") , then a pest might get some crops, but the rest will survive.

I believe that the same principle applies to our financial system.

If power and deposits are concentrated in a handful of mega-banks, problems with those banks could bring down the whole system. As Zandi noted, there is an oligopoly in the banking industry (and "the oligopoly has tightened").

Moreover, the mega-banks are huge holders of derivatives, including credit default swaps. JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and Morgan Stanley together hold 80% of the country's derivatives risk, and 96% of the exposure to credit derivatives.

Even though JP, B of A, Goldman and Citi are separate corporations, they are so interlinked and intertwined through their derivatives holdings that an attack by a "pest" which swarmed in on their derivatives could take down this "monoculture" of overly-leveraged, securitized, derivatives-heavy banking.

Indeed, taking just one example - JP Morgan - independent analyst Reggie Middleton notes:

As of June 30, 2009, JPM had exposure of $85 billion (or 108% of its tangible equity) towards off balance sheet lending commitments and guarantees...

As of June 30, 2009, the total notional amount of derivative contracts outstanding as of June 30, 2009 was about $80 trillion (or 101,846% of its tangible equity)...

Gross fair value (before FIN 39) of the derivative receivables and derivative payables was $1,798 billion (or 2,276% of its tangible equity) and $1,749 billion (or 2,214% of its tangible equity), respectively. The, fair value of JPM's derivative receivables (after FIN 39) was $84 billion (or 106% of its tangible equity) while the fair value of JPM's derivative payables (after FIN 39) was $58 billion (or 73% of its tangible equity). FIN 39 allows netting of derivative receivables and derivative payables and the related cash collateral received and paid when a legally enforceable master netting agreement exists between JPM and a derivative counterparty...

About 23% of the derivative receivables (in terms of fair value after FIN 39) were below investment grade (less than BBB or equivalent) while 12% were rated BBB or equivalent...

Within the dealer/client business, JPM utilizes credit derivatives by buying and selling credit protection, predominantly on corporate debt obligations, in response to client demand for credit risk protection on the underlying reference instruments. Protection may be bought or sold by the Firm on single reference debt instruments ("single-name" credit derivatives), portfolios of referenced instruments ("portfolio" credit derivatives) or quoted indices ("indexed" credit derivatives). The risk positions are largely matched as the Firm's exposure to a given reference entity under a contract to sell protection to a counterparty may be offset partially, or entirely, with a contract to purchase protection from another counterparty on the same underlying instrument. Any residual default exposure and spread risk is actively managed by the Firm's various trading desks. After netting the notional amount of purchased credit derivatives where the underlying reference instrument is identical to the reference instrument on which the Firm has sold credit protection, JPM has net protection purchased of $82 billion along with other protection purchased of $77 billion.

So that's it. They are square, then. Of course unless the sellers of their protection default. If they do, then it may very well cause a daisy chain reaction that could get very ugly ... If you thought Lehman caused problems, compare Lehman's counterparty exposure to JPM's.

The bottom line is that our current banking monoculture threatens not only the biggest banks, but the entire financial system. Pesticides become less effective as pests develop resistance - and, as a byproduct, we poison friendly critters. Likewise, the giants "creatively" work their way around regulations so that the regulations are no longer effective (or at least not enforced, and regulatory capture is widespread. And too much regulation stifles productivity,as an unintended byproduct.

Having power and deposits spread out among more, smaller banks would greatly increase the stability of the financial system. And having more power and deposits in banks using a wider variety of business models (e.g. among banks that aren't heavily invested in derivatives and securitized assets) will create a banking "polyculture" which will lead to a much more stable financial system.

In other words, if we decentralize power and deposits and increase the variety of banking models, we will have a healthier financial system, we won't have such an urgent need to try to micromanage every aspect of the banking system through regulation,and the regulations we do have will be more effective.

By the way, I would argue that that is one of the reasons why Glass-Steagall was so important: it enforced diversity - depository institutions on the one hand, and investment banks on the other. When Glass-Steagall was revoked and the giants started doing both types of banking, it was like a single crop cannibalizing another crop and becoming a new super-organism. Instead of having diversity, you've now got a monoculture of the new super-crop, suscecptible to being wiped out by a pest.

The kinds of things which threaten depository institutions are not necessarily the same type of things which threaten investment banks, hedge funds, etc.

The above is yet another reason we should break up the giant banks using antitrust or other laws.

Note: Wells Fargo's derivatives holdings are substantial, but much less than the other big boys. But rumors are that Wells might be in real trouble as well due to its commercial real estate and other portfolios.

THIS Is How a Congressman Does His Job

Watch Alan Grayson question the general counsel for the Federal Reserve: